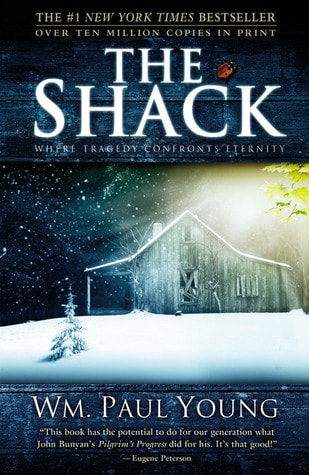

I resisted reading this when it first came out in 2007 and everyone was talking about it. It was very controversial (God as a black female?!) and I heard it wasn’t all that well written. But I found it well worth reading and forgave the didacticism and occasional purple prose for the stimulating way it dealt with ideas. (The plot works way better than The Case for Christ, which, despite agreeing with the conclusions, I didn’t like at all.) “Papa,” the main character’s wife’s name for God, explains her appearance to Mackenzie this way: “I am neither male nor female, even though both genders are derived from my nature. If I choose to appear to you as a man or a woman, it’s because I love you. For me to appear to you as a woman and suggest that you call me ‘Papa’ is simply to mix metaphors, to help you keep from falling so easily back into your religious conditioning…To reveal myself to you as a very large, white grandfather figure with flowing beard, like Gandalf, would simply reinforce your religious stereotypes, and this weekend is not about reinforcing your religious stereotypes.” (205) Judging by the controversy, the author, William Paul Young, succeeded in shaking readers’ stereotypes. Personally, I had no problem with God revealing himself as a woman. Young is not making the Almighty out to be a goddess. Scripture uses female metaphors for God—a nursing mother (Isaiah 49:15), a hen protecting her chicks (Matthew 23:37)—so there is nothing inherently blasphemous in showing God as female. The main character, Mack, had a horribly abusive earthly father. God as Father had always been a struggle for him. Near the end—when Mack is in need of a strong father figure—Papa does appear to him as just that. The book is essentially a discussion of the theological problem of pain in its starkest form—Mack’s little girl is brutally murdered. But the discussion takes place in a strong relational context, showing relationship as essentially the answer to the problem. After receiving a mysterious invitation signed “Papa,” Mack returns to the ramshackle cabin where the murder took place. He is bitter and angry at God for letting this happen. He feels guilty for not protecting his daughter, as does Missy’s older sister Kate whose desire to go canoeing set in motion the string of events that ended in Missy’s death. When Mack wakes next morning, the miserable cabin has been transformed into a place of beauty where he meets “Papa,” a large black woman; Sarayu, an Asian woman hard to pin down who collects his tears in a bottle; and a Middle Eastern man in his 30s—Jesus. When Mack asks, “So which of you is God?” The three answer in unison, “I am.” I loved the loving, affirming, easy-going conviviality shown in the Trinity and the emphasis on relationship over rules. What God wants for us is the same kind of relationships God enjoys in the Trinity. Mack begins to understand that church is “Not a bunch of exhausting work and a long list of demands, and not sitting in endless meetings staring at the backs of people’s head, people he really didn’t even know. [It is] Just sharing life.” (393) Of course, the problem of Missy’s death comes up, not once, but over and over as it does in real-life grief. In one of those conversations, Papa tells Mack, “Just because I work incredible good out of unspeakable tragedies doesn’t mean I orchestrate the tragedies. Don’t ever assume that my using something means I caused it or that I needed it to accomplish my purposes. That will only lead you to false notions about me. Grace doesn’t depend on suffering to exist, but where there is suffering you will find grace in many facets and colors” (410). Like many of us, Mack wonders why Papa doesn’t stop all evil. She responds, “All evil flows from independence, and independence is your choice. If I were to simply revoke all the choices of independence, the world as you know it would cease to exist and love would have no meaning…If I take away the consequences of people’s choices, I destroy the possibility of love. Love that is forced is no love at all” (421-2). Independence is essentially the author’s definition of sin. Hard for Americans to take. Besides Papa, Sarayu and Jesus, Mack encounters Sophia (wisdom) in a beautiful scene in which he gets to see Missy. Sophia challenges him, “Return from your independence, Mackenzie. Give up being [God’s] judge and know Papa for who she is. Then you will be able to embrace her love in the midst of your pain instead of pushing her away with your self-centered perception of how you think the universe should be. Papa has crawled inside of our world to be with you, to be with Missy” (636). This is where things get sticky in my mind. The author’s “Jesus” isn’t concerned with making people Christians. “Those who love me have come from every system that exists. They were Buddhists or Mormons, Baptists or Muslims; some are Democrats, some Republicans and many don’t vote or are not part of any Sunday morning or religious institutions. I have followers who were murderers and many who were self-righteous. Some are bankers and bookies, Americans and Iraqis, Jews and Palestinians. I have no desire to make them Christian, but I do want to join them in their transformation into sons and daughters of my Papa, into my brothers and sisters, into my Beloved [the Church, the Bride of Christ]” (402). Like Mack, this sounds to me like a universalist “all roads lead to God.” “Not at all,” Jesus says. “Most roads don’t lead anywhere. What it does mean is that I will travel any road to find you.” (402) I like that idea. It reminds me of Paul saying, “To those under the law, I became like one under the law… To those not having the law, I became like one not having the law” (1 Corinthians 9:19-21). All things to all people for the sake of the good news. Young says, “Those who love me have come from…”; he doesn’t say they “are” or they “continue in” other cults and religions. “Such were some of you,” Paul reminds the Corinthians after listing sinners who will not inherit the kingdom of God (1 Corinthians 6:9-11). Then Paul goes on to talk about how their lives have been transformed. So I’m not sure the author really is a universalist. He does have Papa say that because of what Jesus accomplished on the cross, “I am now fully reconciled to the world.” Like me, Mack’s eyebrows go up. “The whole world? You mean those who believe in you, right?” Papa replies, “The whole world, Mack. All I am telling you is that reconciliation is a two-way street, and I have done my part, totally, completely, finally. It is not the nature of love to force a relationship, but it is the nature of love to open the way” (425). Calvinists who believe in limited atonement would disagree, but it is a theological question that real believers have wrestled with for hundreds of years. Young’s solution would seem to go along with “Let the one who wishes take the free gift of the water of life” (Revelation 22:17). Mack wants to know if forgiveness necessarily means not being angry. Papa assures him that he should be angry about the terrible thing that was done. “But don’t let the anger and pain and loss you feel prevent you from forgiving him and removing your hands from around his neck” (501). There is no pretence that forgiveness is easy. “You may have to declare your forgiveness a hundred times the first day and the second day, but the third day will be less and each day after, until one day you will realize that you have forgiven completely. And then one day you will pray for his wholeness and give him over to me so that my love will burn from his life every vestige of corruption. As incomprehensible as it sounds at this moment, you may well know this man in a different context one day” (501). In conclusion, I found this book well worth reading, especially if you have wrestled personally with the problem of pain. It’s not a quick read; you will find yourself wanting to savor each tidbit. Young deals with the philosophical problem in a sensitive way that does not minimize the hurt or offer platitudes. He nudges you toward a trusting relationship rather than academic answers. And as Sarayu (Wind, Spirit) says, “Just because you believe something firmly doesn’t make it true. Be willing to reexamine what you believe. The more you live in the truth, the more your emotions will help you see clearly. But even then, you don’t want to trust them more than me” (434). Please begin any comments with "I have read the book..." or "I haven't read the book..." Thank you.

3 Comments

Louise

9/14/2017 02:59:37 pm

I have not read the book, but saw the movie. Just last week, a friend, who I have been praying for, out of the blue watched the movie and asked what I thought of it. I borrowed the movie and was also impressed with much of it. My main objection was Papa's stand that God does not demonstrate His wrath, and thus there is no hell. There is a wonderfully strong emphasis on God's love for even those who do horrible things, but the statement "Sin has its own consequences." sums up the worst that could happen to a person.

Reply

LeAnne

9/15/2017 11:00:05 am

Definitely a problem, Louise. I loved the suggestion that God's love might bring such change in the murderer that Mack would potentially have a different relationship with him. I think of the Serbian ex-soldier my husband met after the Croatian war for independence who looked at his hands and said with tears streaming down his face, "But I have killed so many. How can God accept me?" However, Young doesn't tell us what happens if the murderer continues to reject the transformation of God's love. Heaven would not be heaven if unrepentant murderers were allowed in.

Reply

LeAnne

9/16/2017 08:38:36 am

Here is a more theologically astute review by a friend who teaches at Dallas Theological Seminary. I reposte with his permission. http://www.leannehardy.net/blog/the-shack-review

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLeAnne Hardy has lived in six countries on four continents. Her books come out of her cross-cultural experiences and her passion to use story to convey spiritual truths in a form that will permeate lives. Add http://www.leannehardy.net/1/feed to your RSS feed.

To receive an e-mail when I post a new blog, please subscribe.

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed